It would be tempting—but wrong—to assume

that one VP candidate represents our faith, while the other does not.

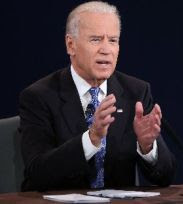

Last week’s Catholic media has been full of politics. Everyone seems to be trying to prove that

their Vice-presidential candidate is a better representative of Catholic

teaching. We even have some bishops proclaiming that Joe Biden cannot receive

communion in their dioceses.

We have known since summer that the presidential race

featured two Catholic Vice-presidential candidates. But only on October 10 did we get to compare and

contrast Joe Biden and Paul Ryan face to face on the subject of their Catholic

faith.

The Vice-presidential debate was nearly over when

moderate Martha Radditz posed this question:

This debate

is, indeed, historic. We have two Catholic candidates, first time, on a stage

such as this. And I would like to ask you both to tell me what role your

religion has played in your own personal views on abortion.

Please talk

about how you came to that decision. Talk about how your religion played a part

in that. And, please, this is such an emotional issue for so many people in this

country...

Although the question focused somewhat narrowly on

abortion--almost as though abortion is the only “Catholic” issue--it also

offered a useful opening for two broader questions: 1. What difference does Catholic

Social Teaching make in their respective political positions? 2.

Which candidate is more consistent and reflecting Catholic social

teaching?

It is instructive, but also surprising, to start with the

answers the candidates gave Radditz. In fact, both candidates answered “Yes,

but…”

Paul Ryan said:

I don't see

how a person can separate their public life from their private life or from

their faith. Our faith informs us in everything we do. My faith informs me

about how to take care of the vulnerable, of how to make sure that people have

a chance in life.

I don't see

how a person can separate their public life from their private life or from

their faith. Our faith informs us in everything we do. My faith informs me

about how to take care of the vulnerable, of how to make sure that people have

a chance in life.

Now, you want

to ask basically why I'm pro-life? It's not simply because of my Catholic

faith. That's a factor, of course. But it's also because of reason and science…Now

I believe that life begins at conception.

That's why --

those are the reasons why I'm pro-life.

Joe Biden said:

My religion

defines who I am, and I've been a practicing Catholic my whole life. And has

particularly informed my social doctrine. The Catholic social doctrine talks

about taking care of those who -- who can't take care of themselves, people who

need help. With regard to -- with regard to abortion, I accept my church's

position on abortion as a--what we call a de fide doctrine. Life begins at

conception in the church's judgment. I accept it in my personal life.

But I refuse

to impose it on equally devout Christians and Muslims and Jews, and I just

refuse to impose that on others…I do not believe that we have a right to tell

other people that -- women they can't control their body. It's a decision

between them and their doctor…I'm not going to interfere with that.

In other words, both candidates were saying, in

effect, that Catholic Social Teaching makes no difference in their position on

abortion. Ryan would be pro-life on

scientific and medical grounds, even if he were not Catholic. And Biden chooses not to apply Catholic

teaching on abortion to public policy.

So in both cases, their political positions are not different because of

their Catholic faith.

Biden did mention Catholic Social Doctrine more

broadly, implying that his overall politics better reflect Catholic Social Teaching

than Ryan’s politics do. But the debate

ended there. This, of course, begs the question: what if we dig deeper?

CrossCurrents readers know my general take on the

relation between Catholic Social Teaching (CST) and our major political

parties: CST does not fit into conventional political categories of “liberal”

or “conservative.” We cannot expect CST to favor either the Democratic or the Republican

platforms.

Consider some major 2012 issues.

“Big Government” or “Small Government”? The general

dividing line between these parties, for example, concerns the size of

government: Democrats favor a larger, more “progressive” government, while Republicans

favor a smaller, less “intrusive” government.

But CST has no preference in principle.

That’s because CST has no doctrine on the best size for government.

Rather, the chief

principle here is “the common good.” All government must serve the common good

as much as possible--and how it does

that is a matter of prudential judgment.

Because government is just a means

to achieve the end of the common

good, it must leave room for other institutions (from families and local

communities on up)--but it must also be powerful enough to address social needs

that other institutions cannot meet. In

CST, there is no magic formula for this.

Taxes: Up or Down? Another debated issue in 2012

is taxes. On this, as on government itself, CST does not lay down any grand

principle. It regards taxes as the main

source for the funding that government needs to do its job. If that job is promoting the common good (in

collaboration with other institutions), then taxes are good insofar as they

enable the common good, and paying taxes is one way that we, as citizens,

support the common good.

Whether any citizen should pay more or less depends on

whether such change would enhance or hinder progress toward the common good of

all. This means that raising and

lowering taxes is never good or better in principle, but depends on the

specific case.

We may debate, then, whether a specific tax hike or tax

cut better serves the common good. But

politicians who pledged never to

raise taxes (as Ryan has) are demonizing

taxes, contrary to CST, rather than seeing them as a potential instrument for

good.

Wealth and Poverty. We hear a lot

in 2012 about the “middle class” and “job creators.” But neither side says much

less about the “working class” or the poor.

Yet CST favors attention to the poor as a top priority. Moreover, CST decries extreme income

inequality between classes. US inequality

has grown steadily since 1970, and ranks worst among advanced industrial

nations. Yet any attempt to close that gap by redistributing wealth, something

CST favors, generally gets labeled “socialism.” In this respect, CST falls to

the left even of the Democratic Party. As

Benedict XVI wrote: “we cannot remain on the sidelines in the fight for justice.”

Human Rights.

The same is true for human rights: As a general rule, the Church’s list of

human rights is considerably longer than either US political party, for while

Americans tend to think only of civil rights (voting, public access, freedom

from discrimination, due process, First Amendment rights), Catholicism also

embraces many economic and social rights: education,

health care, just wages, labor rights, immigration. On many such rights, our popes since 1960

have staked out positions well to the left of the Democratic Party. And these

positions are not merely nice goals; they are matters of principle.

With all this in mind, I’m not terribly surprised that

the debate revealed that, despite their rhetoric, the personal faith of our two

Catholic candidates does not make much difference in their politics. Like most American Catholics, they appear to

get their politics from their parties and other secular sources, not from their

Church (for example, see http://www.onourshoulders.org/

for Ayn Rand’s influence on Paul Ryan,). And like most Catholics, they reinterpret

Catholic Social Teaching to fit their personal politics--or, on inconvenient

issues, they ignore it all together.

© Bernard F. Swain PhD 2012

No comments:

Post a Comment